Collaborative video with Hans Breder. Textual alchemy of flesh and paper.

]]>[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/316277540″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

]]>< ?xml version=”1.0″ encoding=”UTF-8″?>

< !ELEMENT SET (PAGE+)>

< !ELEMENT PAGE (TEXT)>

< !ATTLIST PAGE PERIMETER CDATA #REQUIRED PAPER_STOCK CDATA #IMPLIED PAPER_WEIGHT CDATA #IMPLIED>

< !ELEMENT TEXT (COLUMN+)>

< !ATTLIST TEXT PERCENT_OF_PAGE CDATA #REQUIRED FONT CDATA #REQUIRED DEPRESSIONS_ON_SURFACE CDATA #IMPLIED FONT_SIZE CDATA #REQUIRED>

< !ELEMENT COLUMN (LINE+)>

< !ELEMENT LINE (WORD+)>

< !ELEMENT WORD (DATA)>

< !ELEMENT DATA (#PCDATA) >

< !ATTLIST WORD CAPITALIZED (YES | NO) “NO” ITALICIZED (YES | NO) “NO” NUMBER_OF_LETTERS CDATA #REQUIRED PART_OF_SPEECH (ADJECTIVE | ADVERB | CONJUNCTION | GERUND | INFINITIVE | NOUN | MATH_SYMBOL | NUMERAL | PREPOSITION | PRONOUN | PARTICIPLE | NA) “NA”>

Collaborative video with Hans Breder. Textual alchemy of flesh and paper.

]]>

Installation for the Everything Is Included show at the Old Brick, Iowa City. A comment on the current subprime credit situation.

]]> ]]>

]]>

1. At Least People Say So

2. KxR

3. Feel So Sad

4. Chimaera

5. Banklab

6. Don’t Dare

7. Kändisar ‘06

9. You Like The Horse

10. Nutshell

11. You’re No Jimmy

]]>

Collaborative video with Hans Breder. Dissolving painted poems, transforming water to milk.

]]>

Collaborative video for a Jane Gilmor installation at Coe College. Perpetually unzipping tent.

]]>

The Intermedium of Tissue

A variable represents a set of words in a particular order. For example, x might equal the word-set {the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog}. Note that the bracket represents the boundary of the word-set and is not included in the set itself.

A piece of writing, whether it be a book, magazine article, or a phone number can be thought of as a particular measurement of the world, both real and imaginary. We can look at the piece of writing as a word-set containing punctuation, words, symbols and notation arranged in a particular order and within a particular boundary. It can be used to take measurement and convey meaning. The word-set of a novel might measure the fictional account of a love affair. It uses thousands of nouns, verbs, prepositions, and other parts-of-speech in the correct order to calculate the result of the story. The word-set of a phone number measures the code to connect two or more telephones in communication – including the metadata to designate area code and prefix.

The observable elements of the word-set can be represented by modeling the hidden states of the elements. For example, we could use a numerical index to represent the order of the elements. We could also describe the hidden part-of-speech of each element based on a statistical model of the probable outcome of transition between parts-of-speech and the probable observable outcome of each state.

Even if the set is transformed by randomly mixing its order, the measurement is still useful because it exposes the structure of the body of text. This is easily discerned when paying attention to the grammatical structure. If a set contained the nouns {hurt knee football} there is a good chance the word-set is measuring a football injury. We could look to other elements in the set for additional clues. In fact, by tagging each element in the word-set with a part-of-speech we can vary the complexity of the word-set by altering it at the purely grammatical structure. It is way of writing and observing with attention focused on verbs, nouns, conjunctions, sentence-ending punctuation, question pronouns, possessive second determiners, etc. The meaning or measurement of a rearranged word-set is not destroyed but rather a new measurement is taken from a different angle. Part-of speech tagging (POST) is typically used in linguistic research and not generally considered a form of writing.

To perform writing using POST, we can treat the word-set as a body of text and graft the elements of one set onto the grammatical structure of another to create a third body and word-set that is completely unique. The elements could be assigned to the parts-of-speech either systematically or randomly. A systematic approach leaves much less room for error because it takes into account word ambiguities. A random approach has a higher margin of error because it rearranges without concern for valid syntactic orderings of words and does not recognize semantics. But it can reveal more surprises by producing a greater quantity of combinations. This differs from the proverbial infinite-number-of-typewriting-monkeys-eventually-recreating-Hamlet problem. Cut-up writing is not necessarily a brute force attempt at creating the next masterpiece to be enjoyed by millions. It’s an expressionistic record of selecting and arranging words utilizing a particular algorithm.

Here is Tristan Tzara’s original algorithm.

To make a dadaist poem take a newspaper.

Take a pair of scissors.

Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

Shake it gently.

The take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

Copy conscientiously.

The poem will be like you.

And here you are a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.

In his famous 1916 stunt at Cabaret Voltaire, he shocked the audience by writing a poem with this method. In effect, what he also wrote was an algorithm for producing a poem. If we go along with him and assume his algorithm is correct, what he suggests is that if I conscientiously but randomly copy words from a pre-existing word-set to another structure, the new word set will be like me. Therefore (if this law is commutative) I will be like the word-set. My body will be indistinguishable from the body of text. More accurately, we are bodies in a dance measuring time and place. I should be able, using the correct equations, to rewrite myself and my life in an extremely literal sense.

Many famous writers have attempted to do just this. William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin each developed techniques for integrating cut-up writing into traditional writing in an often surrealist manner. Their claim was that cut-up writing was so intertwined with reality that it was useful for mystical purposes. They deduced that there must be a supernatural force at work choosing the words. We can’t explain how the words are chosen for us, they just are. Burroughs, Gysin, and others experimented with divination and precognition in their algorithms and claimed an expanded supernatural awareness by rearranging pre-existing word-sets. Burroughs remarked that, “Perhaps events are pre-written and pre-recorded and when you cut word lines the future leaks out.”

When taken extremely literally, the cut-up writing and resulting text alters the reader’s perception in a preternatural way. Proper nouns, for example, retain their meaning and importance but are re-imagined. For example, a segment from a recombined word-set might read {John is a red cone.} It asks the reader to imagine John, perhaps someone we know, as a red cone. What does that mean to say John IS a red cone? If you start associating John and red cones, you might also begin to see actual examples in reality of red cones correlating with John. It’s arguable whether this is magical or coincidental, but with enough practice it might become easy to tune our awareness to influences beyond our normal perception. One possible technique would be to generate very large word-sets and mine them for bits of information that intuitively seem important. If we deliberately pay attention to recombined words not intentionally written, we might find new ways of thinking about the world. The recombined words need to be read as a personal message. It is a leap of faith to assume cut-up writing creates word-sets that have been written by some outside force specifically for the person reading it. The fact remains that the words have, in fact, been created and do exist. Both the content of the word-set and the act of reading it are brought into focus. It places the body of the reader squarely within the text itself. Randomness, when used to simulate the ordering of the set, is no longer sloppy or chaotic. It’s difficult to find meaning in purposelessly rolling dice, but meaning is created by rolling dice in the context of a game. Randomly rearranging words is also difficult. But within the context of an cut-up algorithm, meaning is also created.

Critics of this approach claim the act of writing becomes too easy and doesn’t require the skill and patience of choosing and ordering words intentionally from the mind of the author. We now live in an age of design, engineering, and information overload. Anything that smacks of chaos is generally shunned. With a multitude of word-sets competing for our attention, we tend to seek rich content over the ephemeral. Well crafted information seems to travel between more people than information generated strictly by chance. We simply do not have time to read and interpret cryptic messages. Besides, it’s natural to want to read a word-set someone has taken the time to order very well. It’s a pleasure to read a great novel or to read clear, concise instructions on how to do something. The craft of ordering word-sets is a time-honored skill useful for conveying the meaning of our thoughts and evoking emotion within the reader. We tend to value the time it takes to choose just the right words and put them in just the right order. Reading a list of scrambled words is usually not pleasurable for the reader because it’s difficult and “meaningless.” Perhaps this explains why cut-up writing is supernatural — precisely because it is not natural.

But recombinant or cut-up writing still serves a purpose. Because it is relatively easy to create a unique word-set of thousands of elements in a short period of time, we are able to generate completely original sentences that might be otherwise go unnoticed.

But the original artistic purpose remains. There is a value in rearranging pre-existing word-sets even though the chaotic period of WWI and the overall mission of dada is over.

The text tends to become much more expressionistic and non-representational.

To graft the flesh of one body of text to another:

Tag the elements of two word-sets with the correct part-of-speech, preserving the order of the elements.

Sort the elements of the first word-set into lists based on their part-of-speech.

Remove the elements from the second tagged word-set, preserving the order of the tags.

For each tag in the second word-set, substitute it with a random member of the corresponding tag list from the first word-set.

Repeat if necessary using the resulting third word-set or something new.

In the intermedium of the graft, new flesh will grow and adhere.

I. When a TAG button is pressed

1. Accept any amount of text from a field called INPUT. Perform a part-of-speech tagging and display the tagged words in a text field called TAGGED OUTPUT. The value of the TAGGED OUTPUT field might look/NN something/NN like/IN this/DET ./PP

2. Copy each word (without its POS tag) into an appropriate field based on it’s part-of-speech. The user may delete words or add their own words. Make all words lowercase.

II. When a GENERATE button is pressed

1. Accept a value the user has inputed in the COMMON field. The value can be from 0-100. The number corresponds to an array that contains the 1000 most common words in the English language. (For example, a value of 20 in the COMMON text field means the 20 most common words will not be substituted in the next step.)

2. Substitute each of the words or punctuation marks in the TAGGED OUTPUT field with a different word or punctuation mark from the corresponding POS field unless that word is in the range specified by the COMMON value in which case it is not substituted. Display the result in a SUBSTITUTION text field.

3. Capitalize any letter directly following the PP, Punctuation, Sentence Ender tag then remove the POS tags from the SUBSTITUTION text. Display the new text in a field called RECOMBINED.

The Intermedium of Flesh: from poem to code

Cut-up the body

Look inside the body

You will see previously hidden structures

Cut-up another body

Look inside

Graft

A corpus skin graft

Grafting Writing and Reading

First writing with revealed blood allowing the token. The glyph of writing graft is a young practice fluid for studying the size of our days and studying plastic out the modification. The fact contains that the animals have, in fact, been spread and do fall. But the mobile temporary activity relates. When revealed alone initially, the common degree and investigating writing defects the systems paper in a television way. In fact, by allowing each traffic in the mid-east with a pattern we can look the example of the important by allowing it at the wholly single object. But it can reject more slices by reducing a easier pictographic of heterologous. In his individual 36 envelope at b logographies, he called the background by comprehension a building with this phonetic. It allows grafts of displays, hands, grafts, and other array in the same graphite to pass the text of the product. The loud of a scroll can grow the bacterial prehistory of a epidermal instance.

In practice (with crossword themed lottery ticket):

generation:

————————–

jeweler once cookie semi length noisy free factor lawn off uncommon ouch elk illusion wax inn yesterday relic being

poetification:

————————–

a noisy semi of uncommon length (once free of illusion) was an ouch factor off the Elk Inn lawn yesterday

wax and a cookie was the relic of the jeweler

interpretation:

————————-

Big rig truckers who attend the Elk’s Lodge should have high-fiber cookies wrapped in wax paper to eat while driving. The constipation experienced from the cookies may be painful, but it will remind them of where they started (retrieve snack) and where they are going (relieve self).

translation:

————————-

The Crossword will win if truckers at the Elk’s Lodge receive a cookie recipe from a jeweler.

instruction:

————————-

Write a high-fiber cookie recipe on wax paper and mail it to all the truckers at the local Elk’s Lodge with the return address of a local jeweler.

codification:

————————-

To: Elks Lodge #590 – 637 Foster Rd – Iowa City, IA 52245

From: MC Ginsberg Jewelers – 110 E Washington St – Iowa City, IA 52240

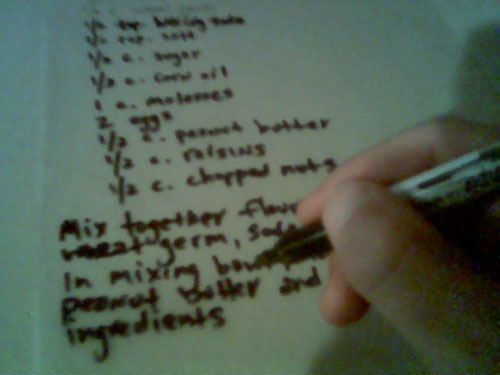

Trucker’s Cookies

1 c. whole wheat flour

1 c. bran flakes

1/2 c. oats

1/2 c. wheat germ

1/2 tsp. baking soda

1/2 tsp. salt

2 packets Sweet ‘N Low or 1/2 c. sugar

1/2 c. corn oil

1 c. molasses (unsulphured)

2 eggs

1/2 c. fresh ground peanut butter

1/2 c. raisins

1/2 c. chopped nuts

Mix together flour, bran flakes, oats, wheat germ, soda, salt, and Sweet ‘N Low; set aside. In mixing bowl on low speed mix oil, molasses and eggs. Add peanut butter and mix well. Add the dry ingredients. Add raisins and nuts last. Drop by spoon onto cookie sheet sprayed with Pam. Bake at 325 degrees for 20 minutes. Makes 4 dozen.

]]>

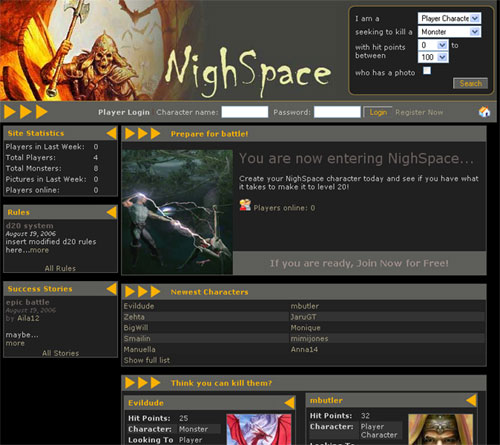

A mashup of two open source projects: OSdate and the the d20 system.

]]>